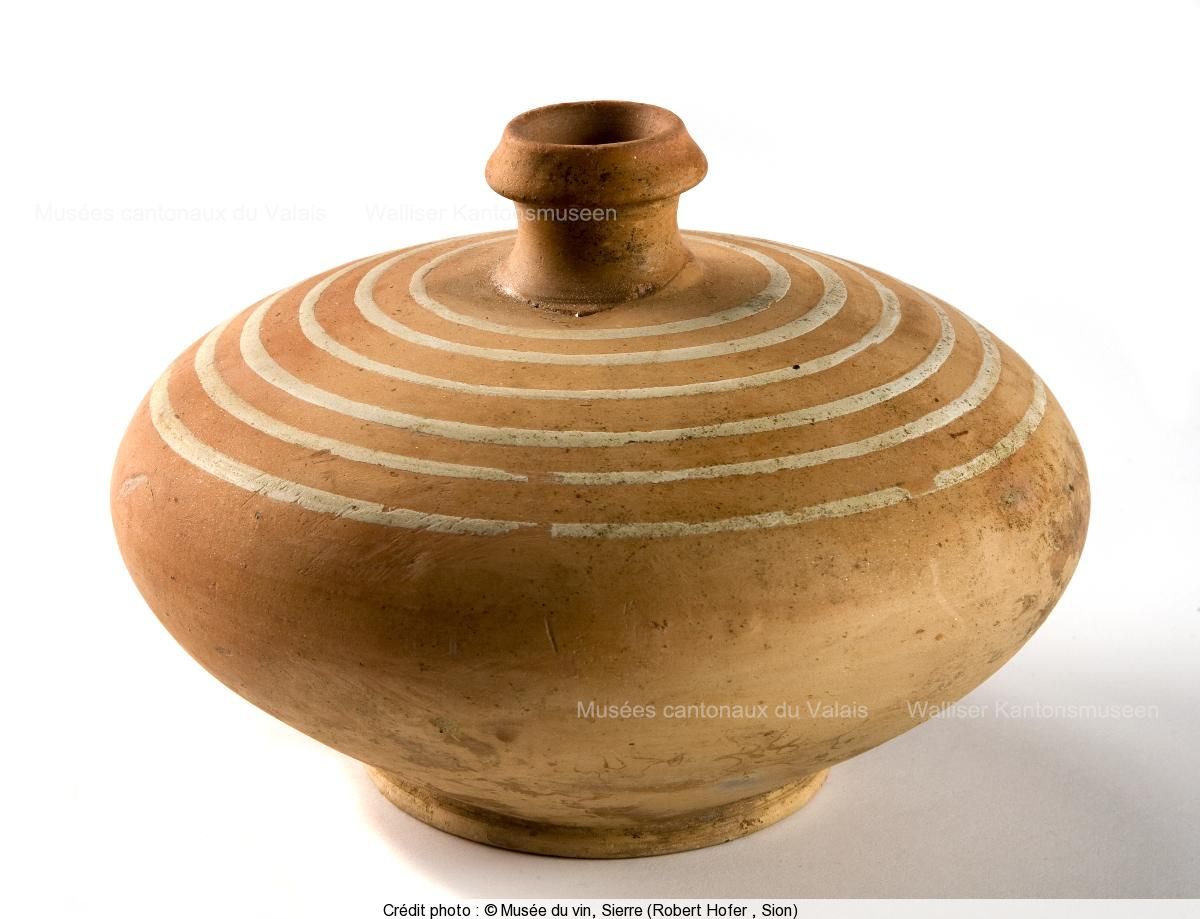

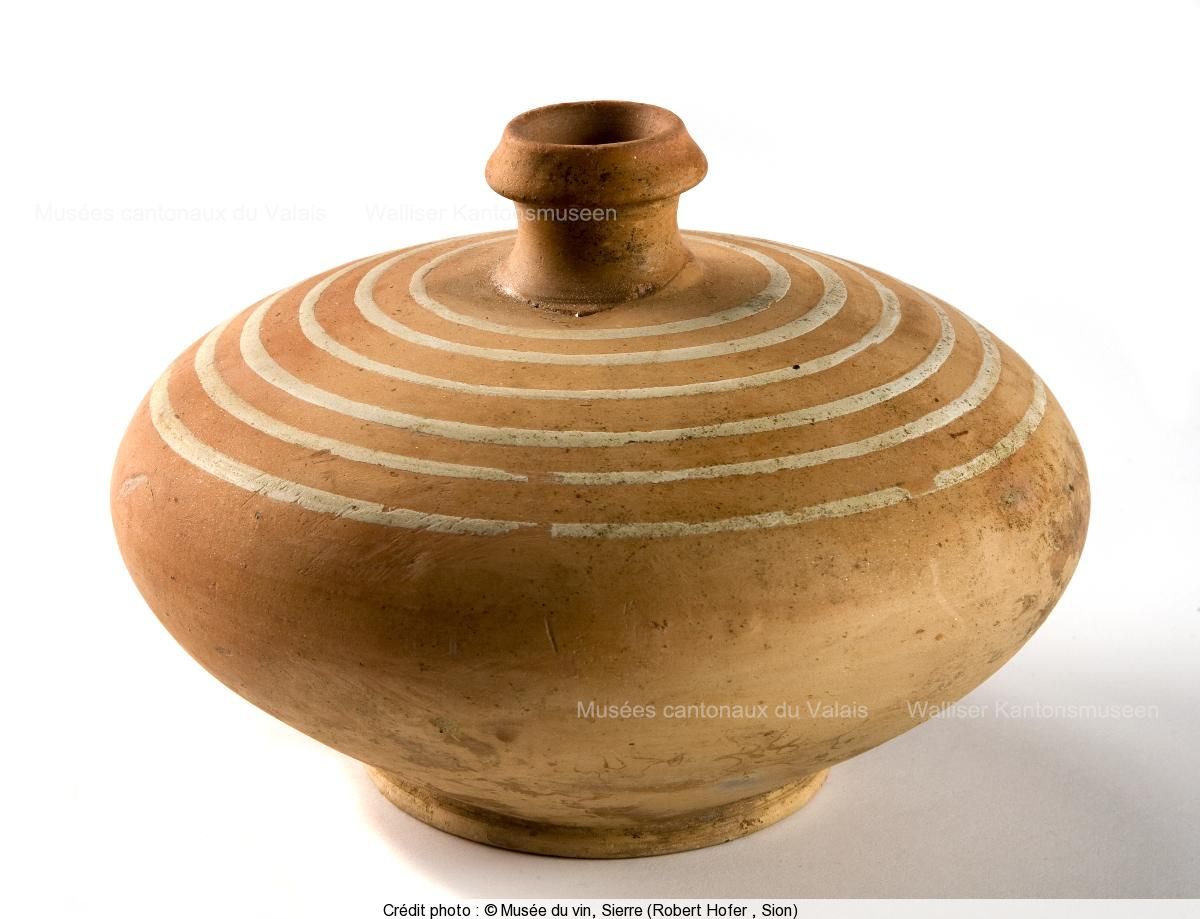

Vase “a trottola”

Philippe Curdy, 2013 :

[NB : notice identique pour 00585, 00942]

Les vases « a trottola », en forme de toupie, sont des récipients produits dans des ateliers d’Italie du Nord dès le IIIe siècle avant J.-C. Leur centre de distribution couvre les régions traversées par le fleuve Tessin, soit l’extrémité sud du canton du Tessin et les parties septentrionales du Piémont occidental et de la Lombardie orientale.

En 1882, on découvre une sépulture à Sembrancher ; le mobilier qui accompagnait le corps du défunt comprenait deux vases «a trottola», deux anneaux de chevilles «valaisans» et deux bracelets en verre brun, dont un seul est conservé au musée. Selon les informations à disposition, il s’agissait d’une tombe féminine, ce que ne contredit pas la présence d’anneaux de chevilles et de bracelets en verre, parures portées par les femmes au cours du second âge du Fer. L’ensemble

peut être daté du IIe siècle avant J.-C., peut-être du milieu du siècle. La présence de tels récipients dans la vallée des Dranses est un fait assez rare pour être souligné.

Les deux récipients présentent une panse bombée, un goulot étroit et une lèvre pendante proéminente ; la panse est décorée de lignes peintes. Avec sa forme très particulière, le vase «a trottola» semble peu adapté à verser des liquides dans un récipient à boire et ferait plutôt office de gourde. Les exemplaires retrouvés au nord de l’Italie présentent très souvent des graffitis gravés sur le haut de la panse : dans la nécropole d’Ornavasso, dans le val d’Ossola, un exemplaire portait une inscription où apparaît le nom uinom (vin) en langue lépontique, une langue pratiquée par les populations de souche celtique installées sur le versant sud des Alpes, au nord des lacs Majeur, de Lugano et de Côme. Ce graffiti prouverait l’utilisation du récipient comme conteneur à vin : les deux vases de Sembrancher sont donc l’un des plus anciens témoignages de la consommation du vin en Valais. En Italie et au Tessin, les nombreux exemplaires recensés concernent presque exclusivement des contextes funéraires : avec d’autres récipients et ustensiles, ils accompagnaient le défunt pour le voyage dans l’au-delà, une coutume propre aux milieux celtiques et méditerranéens. Dans les Alpes suisses, les vases «a trottola» se retrouvent exclusivement en Valais. Quelques pièces sont répertoriées dans le val d’Aoste. Fait particulier à ces deux régions, les ateliers de potier ont réalisé ici des imitations de ce vase en céramique locale, une pratique qui démontre le degré d’assimilation des usages sud-alpins, peut-être un indice supplémentaire à mettre au dossier d’une viticulture précoce dans le Vieux Pays.

Au nord, les vases «a trottola» les plus septentrionaux connus à ce jour au-delà de la barrière des Alpes ont été trouvés au sud de Berne, dans le cimetière celtique helvète de Niederwichtracht d’où proviennent aussi des parures typiquement tessinoises : ce fait illustre bien les liens culturels établis entre la partie méridionale du territoire des Helvètes, le Valais oriental et le Tessin. La distribution des vases «a trottola» permet donc de restituer, traversant le Valais, les voies qui reliaient la plaine du Pô au Plateau suisse par plusieurs cols bien connus, en particulier en Haut-Valais ceux de l’Albrun, du Simplon ou du Monte Moro/Antrona, au sud, et du Grimsel, du Lötschenpass ou de la Gemmi, au nord.

Elsig Patrick, Morand Marie Claude (sous la dir.), Le Musée d’histoire du Valais, Sion. Collectionner au cœur des Alpes, Sion: Musée d’histoire/Paris: Somogy Ed. d’Art, 2013, pp. 72-73.

Philippe Curdy, 2013 :

[NB: gleiche Notiz für 00585, 00942]

Die sogenannten „a trottola“-Flaschen in Kreiselform sind Gefäße, die in Töpferwerkstätten in Norditalien ab dem 3. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert hergestellt wurden. Das Zentrum ihres Verbreitungsgebietes umfasst die vom Fluss Ticino durchlaufenen Regionen, das heißt die Südspitze des Kantons Tessin, den Nordwesten des Piemonts sowie den Nordosten der Lombardei.

Im Jahr 1882 wurde in Sembrancher ein Grab entdeckt. Unter den Grabbeigaben befanden sich zwei Kreiselflaschen, zwei „Walliser Knöchelringe“ und zwei Armringe aus braun gefärbtem Glas, von denen nur einer im Museum erhalten ist. Laut vorhandenen Informationen handelt es sich um die Bestattung einer Frau, wofür die „Walliser Knöchelringe“ und die beiden Armringe aus braunem Glas – beides typischer Frauenschmuck der Jüngeren Eisenzeit – sprechen. Das Fundensemble kann ins 2. Jahrhundert v. Chr. (vermutlich um die Jahrhundertmitte) datiert werden. Das Vorkommen solcher Gefäße im Dransetal ist sehr selten und daher erwähnenswert.

Die beiden Flaschen haben einen gewölbten Gefäßkörper, einen engen Hals und einen ausladenden Rand. Der Gefäßkörper ist mit aufgemalten Linien verziert. Aufgrund ihrer sehr besonderen Form scheint die Kreiselflasche kaum dafür geeignet, Flüssigkeit in ein Trinkgefäß zu gießen, und dürfte eher als eine Art Feldflasche gedient haben. Die in Norditalien vorgefundenen Exemplare tragen sehr oft Graffiti auf dem oberen Gefäßkörper. Auf einer Kreiselflasche vom Gräberfeld von Ornavasso im Ossolatal steht die Inschrift „uinom“ (Wein) in lepontischer Schrift. Die Sprache wurde von Gruppen keltischen Ursprungs, die sich an der Südseite der Alpen nördlich des Langen-, Luganer und Comer Sees angesiedelt hatten, gesprochen. Das Graffito vermag die Verwendung des Gefäßes als Weinbehälter zu belegen; die beiden Gefäße aus Sembrancher wären demnach die ältesten Zeugnisse für den Konsum von Wein im Wallis.

Die zahlreichen in Italien und im Tessin registrierten Exemplare stammen fast ausschließlich aus Grabkontexten. Zusammen mit anderen Gefäßen und Utensilien begleiteten sie den Verstorbenen auf seiner Reise ins Jenseits, ein Brauch, der bei den Kelten und den antiken Kulturen des Mittelmeerraumes üblich ist. In den Schweizer Alpen treten Kreiselflaschen ausschließlich im Wallis auf. Einige weitere sind im Aostatal bekannt. In den Töpferwerkstätten beider Regionen wurde dieses Gefäß imitiert und aus lokalem Tonmaterial gefertigt. Dies zeigt, wie sehr südalpine Gebräuche übernommen wurden; vielleicht ein weiterer Hinweis auf einen frühen Weinbau im Wallis.

Die bis heute nördlichsten Funde von Kreiselflaschen diesseits der Alpen stammen vom helvetischen keltischen Gräberfeld von Niederwichtracht südlich von Bern, von dem auch Tessiner Schmuck bekannt ist. Dies unterstreicht die kulturellen Verbindungen, die zwischen dem südlichen Gebiet der Helvetier, dem Ostwallis und dem Tessin bestanden. Die Verbreitung der Kreiselflaschen ermöglicht es demnach, die Routen durch das Wallis zu ermitteln, die die Poebene über mehrere Pässe im Oberwallis mit dem Norden verbunden haben, insbesondere über den Albrun-, Simplon- und Monte Moro- / Antronapass im Süden sowie den Grimsel-, Lötschen- und Gemmipass im Norden.

Elsig Patrick, Morand Marie Claude (Hrsg.), Das Geschichtsmuseum Wallis, Sitten. Sammeln inmitten der Alpen, Sitten: Geschichtsmuseum Wallis/Paris: Somogy Ed. d’Art, 2013, S. 72-73.

Philippe Curdy, 2013 :

[NB: same note for 00585, 00942]

The pegtop-shaped “a trottola” vases are containers manufactured in North Italian workshops from the 3rd century BC on. The centre of their distribution covers the areas through which the Ticino River flows, i.e. the southern tip of the canton of Ticino and the northern parts of Western Piedmont and Eastern Lombardy.

In 1882, a burial was discovered at Sembrancher; the grave goods accompanying the deceased comprised two “vases a trottola”, two “Valaisan” anklets and two bracelets made from brown glass, of which only one is preserved in the Museum. According to the information available, it was a female burial, which is indicated by the presence of anklets and glass bracelets, ornaments worn by women during the Late Iron Age. The assemblage can be dated to the 2nd century BC, perhaps to the mid-century. The presence of such containers in the Dranse valley is a rather rare finding which deserves to be mentioned.

Both containers have a rounded body, a straight neck and a wide overhanging rim; the body is decorated with painted lines. Due to its particular shape, the “a trottola” vase seems to be little adapted to pouring liquids into drinking cups and rather served as a flask. The specimens currently discovered in Northern Italy have graffiti engraved in the upper part of the body: in the Ornavasso cemetery in the Ossola valley, a piece bore an inscription on which the word uinom (wine) appears in Lepontic, a language spoken by populations of Celtic origin established on the southern face of the Alps, north of the Lakes Maggiore, Lugano and Como. This graffiti may approve the use of the vase as a container for wine: the two vases from Sembrancher are thus the earliest evidence of wine consumption in the Valais.

In Italy and in the Ticino region, the numerous recorded specimens almost exclusively stem from funerary contexts: along with other vessels and utensils they accompanied the deceased during his journey to the afterlife, a custom specific to Celtic and Mediterranean societies. In the Swiss Alps, the “a trottola” vases are found only in the Valais. Some pieces are recorded from the Aosta Valley. As a matter of fact, imitations of this vase type, common to both regions, were made from local materials in potters’ workshops, a practice that demonstrates the degree of assimilation of south-Alpine practices, and is perhaps an additional indication of early viticulture in the Valais.

The northernmost “a trottola” vases known were actually discovered south of Bern in the Celtic Helvetic cemetery of Niederwichtracht from where typically Ticino ornaments also originate: this fact clearly illustrates the cultural relationships established between the southern part of the Helvetii territory, the Eastern Valais, and the Ticino. The distribution of “a trottola” vases thus allows us to reconstruct the routes in the Valais which linked the Po plain to the Swiss plateau by a series of well known passes, more particularly in the Upper Valais, those of Albrun, Simplon and Monte Moro/Antrona in the south, and of Grimsel, Lötschenpass and Gemmi in the north.

Elsig Patrick, Morand Marie Claude (Ed.), History Museum of Valais, Sion. Collecting in the heart of the Alps, Sion: Musée d’histoire/Paris: Somogy Ed. d’Art, 2013, pp. 72-73.