Statue

François Wiblé, 2013 :

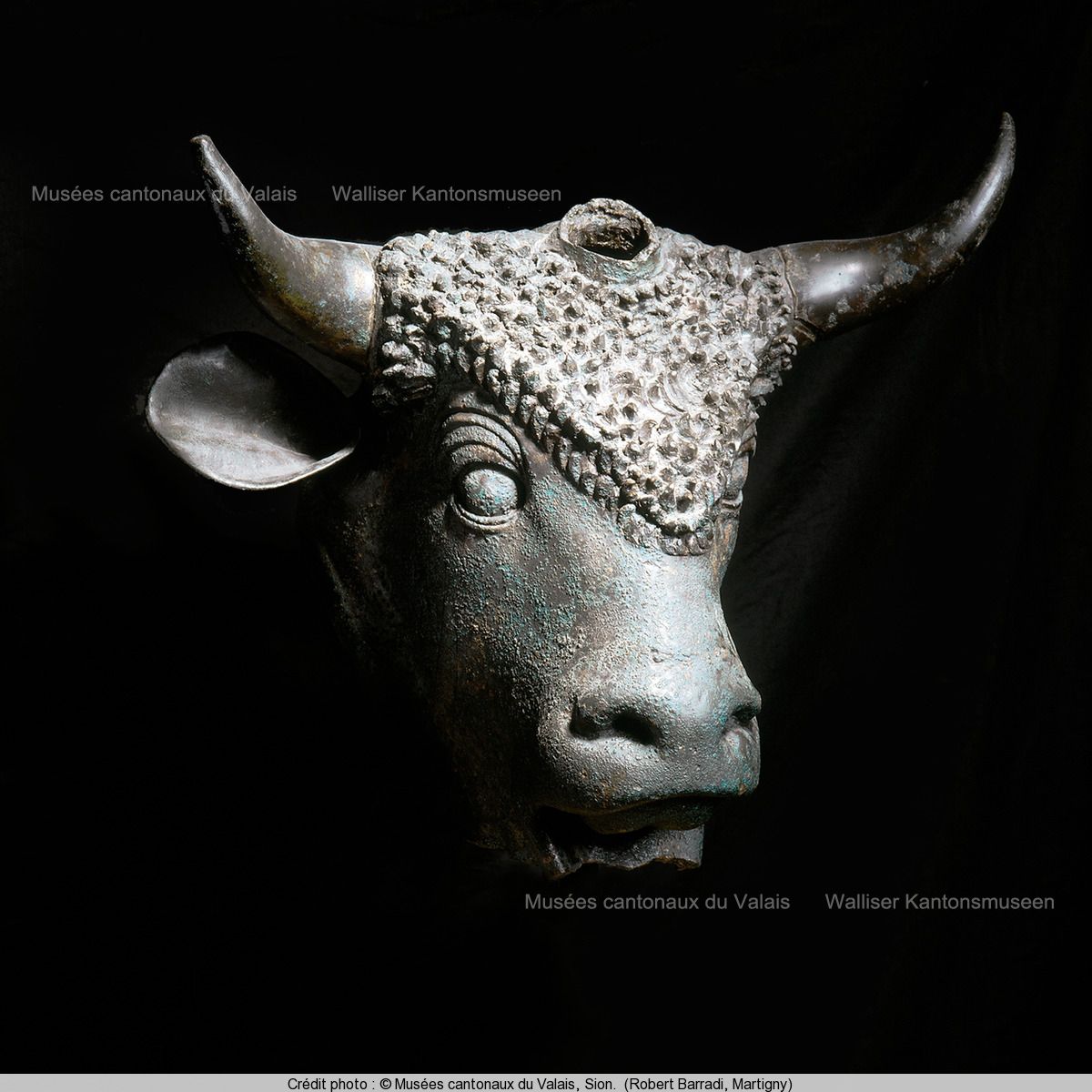

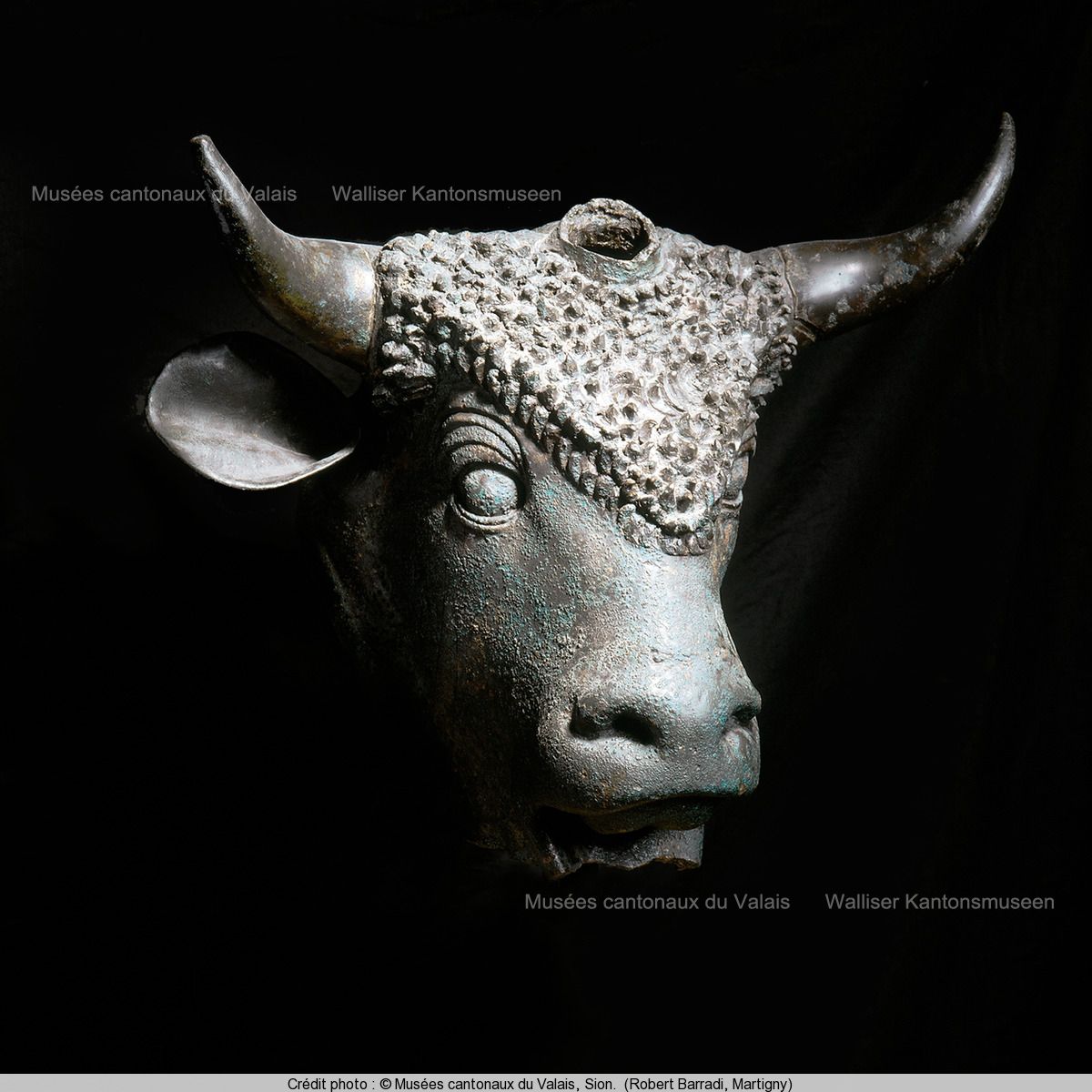

De cette tête de taureau grandeur nature, il manque l’oreille gauche et la corne frontale, dont on distingue très bien l’arrachement. Les cornes sont très écartées et l’oreille est plutôt petite. Les touffes de poils du front sont formées de nombreuses bouclettes triangulaires. Les grands yeux ovales sont soulignés par des lignes en demi-cercles bien marquées, de manière stylisée, tandis que le rendu des naseaux est réaliste.

Exprimant depuis des temps immémoriaux la force, la combativité, la fécondité, le taureau est avant tout un animal sacré ou divin. Les nombreuses statuettes qui le représentent retrouvées dans nos régions ont toutes les chances d’avoir appartenu au mobilier d’un sanctuaire ou d’un autel domestique. Quelques-unes portent une troisième corne sur le front.

Le taureau tricorne est un animal sacré gaulois, dont le nom ne nous est pas parvenu et que l’on vénérait à l’époque romaine surtout dans la Gaule de l’Est et du Nord, ainsi que sur le Plateau suisse. Près de chez nous, on en a retrouvé des figurations à Vidy/Lousonna, à Vallon, à Baden/Aquae Helveticae et à Augst/Augusta Raurica, près de Bâle.

Le taureau de Martigny en est la seule représentation grandeur nature qui ait été conservée. C’était certainement une statue de culte, associée peut-être à Mercure, auquel pourraient appartenir deux fragments d’une statue colossale en bronze faisant partie du même lot, enfouis probablement par un bronzier en vue de sa récupération. Ce devait être à l’époque chrétienne déjà, car on imagine mal une destruction de statues de culte auparavant. La représentation la plus accomplie de l’animal sacré est une statuette découverte à Avrigney en Haute-Saône (musée de Besançon) ; longue de 75 cm, elle permet de se faire une bonne idée de l’allure du taureau de Martigny. Les autres statuettes sont souvent de médiocre qualité.

La troisième corne affirme d’autant plus le caractère sacré de l’animal que l’on connaît l’importance du chiffre trois pour les Gaulois : divinités tricéphales, triades divines, etc. Tripler la corne du taureau,

c’est exalter sa puissance surnaturelle en plus de sa force, de sa combativité et de sa fécondité.

Le socle d’une petite statuette en bronze conservée au musée d’Autun porte une dédicace à l’empereur, sans mentionner le nom sous lequel l’animal était connu. Le fait que cet objet ait été consacré à l’empereur, dieu vivant, laisse supposer que le taureau n’était pas considéré lui-même comme une divinité. Le taureau tricorne n’apparaît pas dans des contextes qui permettraient de l’associer sûrement à un dieu du panthéon gallo-romain. Dans la mythologie classique, le taureau est associé à la mer, aux eaux courantes, à un torrent impétueux ; on a ainsi pu penser que la statue de Martigny pouvait évoquer le Rhône.

Dans les régions alpines, de nombreux toponymes sont formés à l’aide d’une ancienne racine tauru ou tarvo, désignant le taureau, comme cette montagne en aval de Martigny (ce serait le Grammont, de préférence à une des Dents du Midi) appelée Tauredunum, qui s’est écroulée dans la plaine du Rhône au VIe siècle après J.-C.

Elsig Patrick, Morand Marie Claude (sous la dir.), Le Musée d’histoire du Valais, Sion. Collectionner au cœur des Alpes, Sion: Musée d’histoire/Paris: Somogy Ed. d’Art, 2013, pp. 86-87.

François Wiblé, 2013 :

An diesem Stierkopf in Lebensgröße fehlen das linke Ohr und das vordere Horn, dessen Ausrissspuren sehr deutlich sichtbar sind. Die Hörner sind weit nach außen gebogen, und das (erhaltene) Ohr ist eher klein. Die Haarbüschel an der Stirn sind durch unzählige dreieckige Löckchen dargestellt. Die großen ovalen Augen sind sehr stilisiert und durch deutlich markierte Halbkreislinien betont, während die Wiedergabe der Nüstern sehr realistisch ist.

Seit undenkbaren Zeiten Kraft, Kampflust und Fruchtbarkeit verkörpernd, ist der Stier vor allem ein heiliges oder göttliches Tier. Die zahlreichen Statuetten, die in unseren Regionen gefunden wurden, haben mit größter Wahrscheinlichkeit zur Ausstattung eines Heiligtums oder eines Hausaltars gehört. Einige von ihnen besitzen ein drittes Horn auf der Stirn. Der dreigehörnte Stier ist bei den Kelten ein heiliges Tier, dessen Name nicht überliefert ist und das in der Römerzeit vor allem in Ost- und Nordgallien sowie im Schweizer Mittelland verehrt wurde. Nicht weit vom Wallis finden sich Stierfigürchen in Vidy / Lousonna, in Vallon, in Baden / Aquae Helveticae und in Augst / Augusta Raurica bei Basel.

Der Stier aus Martigny ist die einzige Wiedergabe in Lebensgröße. Es handelte sich mit Sicherheit um eine Monumentalstatue, vielleicht des Gottes Merkur, zu der zwei Bronzefragmente gehören, die zusammen mit dem Stierkopf Teil desselben Bronzehortes waren. Vermutlich handelt es sich um den Verwahrort eines Bronzegießers. Der Fund kann erst in frühchristlicher Zeit vergraben worden sein, da eine Zerstörung von Kultstatuen vorher kaum vorstellbar ist.

Die gelungenste Wiedergabe des heiligen Tieres ist eine kleine Statue, die in Avrigney in der Haute- Saône (Museum Besançon) gefunden wurde. Sie ist 75 cm lang und erlaubt eine Vorstellung des Aussehens des Stieres von Martigny. Die übrigen Statuetten sind oft von minderer Qualität. Das dritte Horn bestätigt den heiligen Charakter des Tieres, vor allem wenn man die Bedeutung der Zahl drei bei den Kelten berücksichtigt: dreiköpfige Gottheiten, Göttertriaden usw. Das Horn des Stieres zu verdreifachen kommt einer Steigerung seiner übernatürlichen Kraft gleich, zusätzlich zu seiner Kampflust und Fruchtbarkeit. Das Podest einer kleinen Statue aus Bronze, die im Museum von Autun aufbewahrt ist, trägt eine

Widmung an den Kaiser, ohne den Namen, unter dem das Tier bekannt war, zu erwähnen. Die Tatsache, dass dieser Gegenstand dem als Gott verehrten Kaiser gewidmet war, lässt den Schluss zu, dass der Stier selbst auch als Gottheit betrachtet wurde. Der dreigehörnte Stier tritt jedoch nicht in Kontexten auf, die es erlauben, ihn mit einer bestimmten Gottheit des keltischen Pantheons zu assoziieren.

In der klassischen Mythologie wird der Stier mit dem Meer, den Wasserläufen oder Sturzbächen verbunden. Es ist daher denkbar, dass die Statue aus Martigny möglicherweise die Rhone verkörpert. Im Alpenraum sind zahlreiche Ortsbezeichnungen mit der antiken Wurzel tauru oder tarvo, das heisst Stier, bekannt. So wird zum Beispiel ein Berg unterhalb von Martigny, der im 6. Jahrhundert n. Chr. in die Rhoneebene gestürzt ist (es dürfte sich eher um den Grammont als um einen der Dents du Midi handeln), Tauredunum genannt.

Elsig Patrick, Morand Marie Claude (Hrsg.), Das Geschichtsmuseum Wallis, Sitten. Sammeln inmitten der Alpen, Sitten: Geschichtsmuseum Wallis/Paris: Somogy Ed. d’Art, 2013, S. 86-87.

François Wiblé, 2013 :

The left ear and frontal horn of this lifesize bull head are missing, with traces of the detachment clearly visible. The horns are spaced quite far apart and the ear is rather small. The tufts of hair are formed by numerous small triangular curls. The wide oval-shaped eyes are emphasized in a very stylized manner by well-marked semicircular lines, whereas the finishing of the nasals is very realistic.

Symbolic of strength, fighting spirit, and fertility from time immemorial, the bull is first and foremost a sacred or divine animal. The numerous statuettes found in our regions depicting the bull were most likely part of the equipment of a sanctuary or a domestic altar. Some of them have a third horn placed on the forehead. To the Gauls, the three-horned bull was a sacred animal whose name has not been preserved and which was venerated during the Roman period, notably in Eastern and Northern Gaul as well as on the Swiss plateau. Images have been found close to the Valais, at à Vidy / Lousonna, Vallon, Baden /Aquae Helveticae and Augst /Augusta Raurica, near Basel.

The bull from Martigny is the only preserved full-size representation we have. It was certainly a cult statue, perhaps associated with Mercury. Two fragments from the same assemblage may belong to his monumental bronze statue, probably a hoard buried by a bronze smelter. This could have occurred only during the Christian era, as cult statues were hardly ever destroyed before then.

The most accomplished representation of this sacred animal is the statuette discovered at Avrigney in the Upper Saône area (Museum of Besancon); it is about 75 cm in height, and looks somewhat like the bull from Martigny. The other statuettes are often of poor quality. The third horn confirms the sacred nature of the animal, in particular considering the importance of the number three to the Gauls: three-headed divinities, divine triads, etc. The third horn of the bull means that its supernatural power has been added to its virtues of strength, fighting spirit and fertility. The pedestal of a small bronze statuette kept in the museum of Autun bears an inscription dedicated to the emperor without mentioning under which name the animal was known. The fact that this object was consecrated to the god-like emperor supposes that the bull itself was not considered as a divinity. The three-horned bull does not appear in contexts that would allow us to definitely link it to one special god or goddess in the Gallo-Roman pantheon.

In classical mythology, the bull is associated with the sea, rivers, torrents; it was put forward that the statue from Martigny may evoke the Rhone River. In the Alpine regions, numerous toponyms were built with an ancient radical tauru or tarvo, designating the bull from the mount downstream from Martigny, for example (probably the Grammont, rather than one of the Dents du Midi) called Tauredunum, which collapsed into the Rhone plain during the 6th century BC.

Elsig Patrick, Morand Marie Claude (Ed.), History Museum of Valais, Sion. Collecting in the heart of the Alps, Sion: Musée d’histoire/Paris: Somogy Ed. d’Art, 2013, pp. 86-87.